How to Use Assertiveness to Your Advantage

Are you tired of being told that you need to be more assertive? It turns out that you might have had the mix right all along.

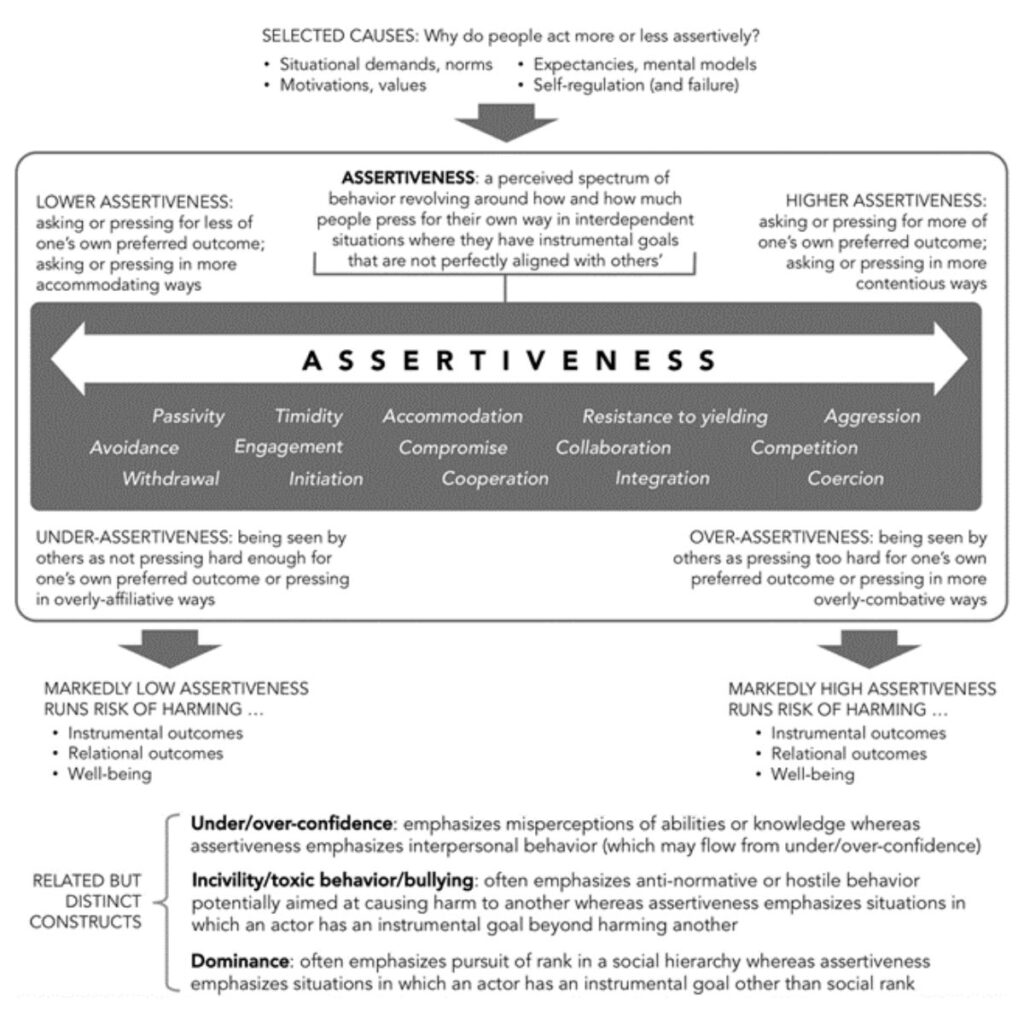

Interpersonal assertiveness is the degree to which you or I seek to fulfil our own interests over those of others.

Most people would say that being assertive is a good thing. Women, especially, are continuously told to act more assertively, that we must stand up for ourselves, or we’ll never get anywhere in this world, and to fight for “our truth”. Assertiveness is a revered quality.

“Sometimes it’s a dog-eat-dog world and the rest of the time it’s the other way around.”

Lawrence Block, A Dance At The Slaughterhouse

There are common stereotypes of what assertiveness looks like in action. For instance, if you asked me to name an extremely assertive movie character, my mind goes quickly to Gordon Gecko in Wall Street or Miranda Priestly in The Devil Wears Prada.

Gecko and Priestly are brutally assertive – blunt, ruthless, and elitist. They always get what they want and chop off the careers of anyone who fails them.

Stereotypes also tend to mock people with low assertiveness. Priestly’s personal assistant, Emily Charlton, is a good example. Charlton fears and reveres Priestly, which makes her incapable of pushing back against Priestly’s demands. Charlton is Priestley’s simpering lapdog who savagely defends her territory for fear of losing everything and has no life outside of work.

While these extremes of assertiveness make for great movie characters, research shows that regardless of whether you are the winner or loser, operating at the extremes delivers poorer results.

I’ll step you through an example to show you why.

“There is ample evidence that extremes—in both aggressiveness and accommodation—carry downside risks for nearly everyone.”

Ames, D., Lee, A., & Wazlawek, A. (2017)

The scene: We’re going on an adventure

Imagine you and I are old school buddies, sitting in a café. It’s been a decade since we spent quality time together; life, families, you know how the story goes. We’ve stayed in contact but haven’t found the time to reconnect properly, and that’s why we are in the café.

We’ve decided to go on an adventure together, reliving some fun we had at school. On the phone, we chatted about dusting down our backpacks, pulling on our walking boots and heading off for three weeks to explore the world.

The purpose of the cafe meeting is to catch up face-to-face and decide the destination.

“Where would you like to go?” I ask.

“Europe.”, you reply. “Poland or Slovenia, ideally. I’ve always wanted to go there.”

“What about you?”

“I’ve been dreaming about Central America.”, I reply.

Our adventure has reached a crossroads, and to move forward, we must agree on the destination. We pause to consider each other’s perspective.

Now, let’s look at three ways we could respond.

Scenario 1: You win

Even though we haven’t met face-to-face for years, I’ve followed you on social media and witnessed how hard you’ve worked while also raising a family. You deserve the break more than I do. I can’t afford to go to Europe, but if that’s what you truly want, I’ll find a way to pay for it.

“Going to Central America can wait for another day, let’s do Europe.”, I reply.

You accept the offer without hesitation.

Analysis

Low assertiveness shows up in a person’s behaviour in many ways, including:

- Avoiding confrontation,

- fear of rejection,

- timidity or

- readily relinquishing to others’ demands.

Obviously, my low assertiveness delivers bad outcomes for me. Our trip will see me creating a bad debt, visiting a place I can’t afford to enjoy, and consequently resenting our friendship.

But you may not notice that my behaviour also delivers poor results for you. I said yes to what you wanted, which seems a good result for you. But is it the best result?

When I quickly say yes to your request, your ideas remain undeveloped, which often means some risks remain hidden and valuable options are left behind.

For example, you don’t know about my financial constraints because you took the easy win. You plan the holiday of a lifetime, thinking that I have money to burn. I agreed to go, didn’t I? So you assume I must be able to afford it. Part way through the holiday, my small cash reserves bottom out, leaving us stranded, or I spend the whole trip skimping, which kills the experience for you.

Note: When someone readily yields to what you want, try to resist thinking of it as a win and start asking exploratory questions. You might uncover a far better result.

Scenario 2: I win

I absolutely don’t want to go to Europe. I decide to tell you all the problems with going there, hoping you’ll agree with my point of view.

“Who can afford Europe right now?” I reply. “The dollar is weak, and airfares a horrendously expensive. I visited Slovenia a while back. It’s seriously boring: full of pale tourists and tacky souvenir shops.”

The look on your face is a mix of shock and bewilderment.

“But Central America will be challenging,” you reply, “I want to relax; it’s meant to be a holiday.”

“I thought you wanted an adventure?” I counter-argue. “Have you lost your spine?”

You agree to go to Central America.

Analysis

In this scenario, I use coercion to push for my outcomes; I undermine your opinions and belittle how you feel to get my own way.

Coercion is a form of high assertiveness along with:

- competitiveness,

- aggression, and

- domination.

While some might revere my toughness, research shows that over-assertiveness in negotiation causes short- and long-term losses.

For instance, my hardcore tactics might have you agreeing to Central America while we are at the café, but that changes soon after when you’ve had time to think and get feedback from others. After that, you stop returning my calls, and our friendship and adventure fade into history. Furthermore, you may also tell all our friends how much of a dirtbag I was to deal with, and they’ll all opt out of doing anything with me in the future.

“Stepping back, we see that, like low assertiveness, high assertiveness can jeopardise instrumental outcomes (e.g., by provoking resistance, impasses, or retaliation), can undermine relationship outcomes (e.g., by damaging trust), and can hamper well-being (e.g., by stoking stress-inducing conflicts).”

Ames, D., Lee, A., & Wazlawek, A. (2017)

In short, nobody likes to interact with a bully and will rebel against that type of pressure with whatever means they have.

Scenario 3: A fantastic alternative wins

I break the silence by asking you a question.

“What attracts you to places like Slovenia and Poland?”

We discuss the destinations and discover our shared passion for mountains and cultural history.

Then you ask the same of me.

“Central America has rich history as well and I love the coastline.”, I reply. “I can also afford it. I’ve just started a new business, and that’s burning through my cash reserves.”

You acknowledge we won’t have fun travelling if we are worried about money all the time, so we dream up other alternatives that have mountains, cultural history, and coastline and are affordable. Eventually, we agree that India is an excellent place for our adventure and put Europe and Central America on the bucket list for the years to come.

Analysis

This scenario is an example of adaptive assertiveness.

Adaptive assertiveness is the midpoint between high and low assertiveness and focuses on clarifying purpose, setting boundaries and conceding wisely. For example:

- We explored what was important about the destinations we tabled

- I set boundaries around spending money because I don’t have much, and

- You accepted that as a valid issue and conceded the idea of travelling to an expensive location.

Adaptive assertiveness isn’t just a case of splitting the difference, which means you get some of what you want, and I get some of what I want. If we had split the difference, we might have agreed to spend ten days in Slovenia and then fly to Central America. We would have burned a lot of money on airfares, suffered jetlag, wasted hours in airports and probably not seen the mountains we love so much.

Instead, we got clear about our purpose, set some boundaries and then brainstormed options that fitted into that frame. As a result, we have an adventure planned that is a recipe for a great holiday.

You can’t always get what you want

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards

But if you try sometimes, well, you might find

You get what you need.

There’s a twist in the story

As I said earlier, people often criticise women for lacking assertiveness, and if they think effective assertiveness is Gordon Gecko, then they are probably right. But as we often see in the movies and the example above, people who exert that style of control over others often end up in bad places, physically and psychologically.

Research shows that genuinely effective assertiveness requires:

- emotional regulation and intelligence,

- adaptability, and a

- quiver full of negotiation techniques that you can draw on.

When I look through that list, I see many women I know. They are quiet achievers who can navigate challenging, complicated scenarios with stellar results. Are women assertive? They’re champions at it.

Reference

This story draws key information from:

Ames, D., Lee, A., & Wazlawek, A. (2017). Interpersonal assertiveness: Inside the balancing act. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11(6), e12317. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12317